One thing that comes up a lot in any sort of software engineering is the concept of automation: how can we take repetitive, error-prone tasks and automate them? This is where you get things like automated testing and automated build systems. It’s also part of why the LLM nonsense known as “AI” has taken over billionaires’ brains: the idea of replacing their “entitled workers” with slop is just too enticing, apparently.

There’s also the idea that in a lot of projects, especially programming and game development, that the last 20% of the work takes 80% of the time. (Sometimes it’s 80 out of 100, sometimes it’s an additional 80%, but either way it’s a lot.) So combining these two ideas: what if we could get away with just doing that first 80% of the work? Or to put it another way, can we get away with half-assing automation?

I would argue, yes. Especially in “solo” development, there are so many things to do, and only so much time to use, so you have to at least try and use your time wisely. I’m going to go through two examples of what I call semi-automation, one I did for Iron Village and one that I’m working on for project OY.

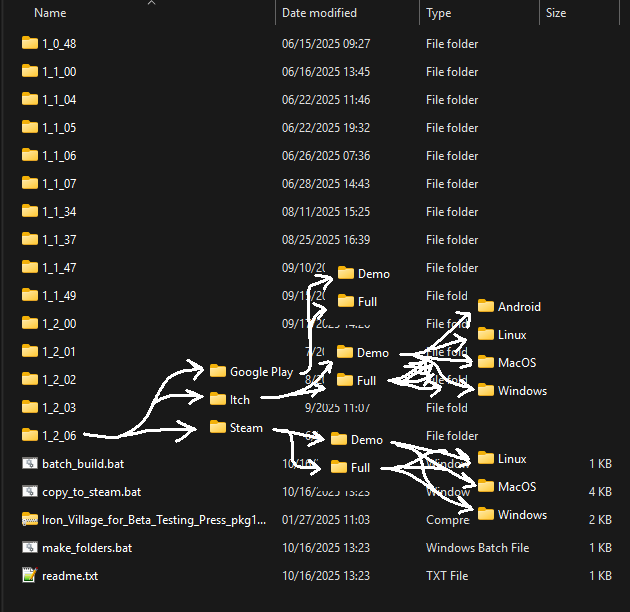

To start, Iron Village. As you may know, Iron Village is available for a few different platforms: Windows, MacOS, Linux, and Android. (Technically Android is built on top of Linux, but it’s different enough to require its own build. On the flip side, the Steam Deck just runs Linux, and can handle a lot of Windows programs as well, so that gets covered pretty easily.) Each of these platforms works differently, so the actual executable program needs to be built differently for each one. That’s 4 different builds so far.

Next though, there’s three different stores: Steam, Itch, and Google Play. The fun thing is that each one gets built differently: the Steam version has its SDK plopped in so that you get achievements and cloud saves. Same deal for Google Play, it gets its own SDK that works slightly differently, although I haven’t been able to get cloud saves to work. (I might need to tinker with the plug-in that allows Hoodie to use the Android SDK to get more debugging info, but it’s been low priority.) The Itch version doesn’t need any of that, so it builds without the extra stuff. Not every store supports every platform, but that gets us up to 8 different builds: Steam Windows, Steam MacOS, Steam Linux, Itch Windows, Itch MacOS, Itch Linux, Itch Android, Google Play Android.

But wait! There’s also a demo. Similar build system there, but there’s a flag that gets set and some assets from the later levels are stripped out. So multiply the earlier number by 2 and you get… 16 different builds. There’s no way to do that one at a time and keep your sanity, especially when you have to repeat the process for every update.

So ok, this has got to be automated, what are the easiest wins we can get? I was having issues running Godot from the command line, for some reason, but the export section allows you to “Build All”, so that’s what I did. It’s a little annoying because there MacOS build on a Windows machine seems to be broken, but everything else works. This means the computer wastes time on making builds it doesn’t need, but it saves us from having to click and wait 12 separate times, so it’s still a win.

Before that, I do also have to manually update the output location for each version (that’s how I have my output folders structured). That could be automated in the future, but it’s a little trickier because you have to read through and modify an existing file, so that work gets indefinitely postponed. Making the folders is automated though, it’s a pretty simple batch script.

So we have the folders set up, everything is built and in place, and… Oh right, MacOS. If Lunar Chippy Games were a larger company, we might have a separate build server (potentially on the “cloud”), probably running Linux (although MacOS could be an option if the MacOS build is also broken on Linux), and everything would be in one place. However, that requires more setup work, as well as money, so our semi-automation system will skip all of that. Instead, I open up my MacBook (shout out to Toast for letting us keep those when they laid off half the company at the start of the pandemic), pull all the commits, build x4, and paste the results in Google Drive. Is this efficient? No. But it’s a harder thing to automate, and it’s only 4 builds, so it’s not worth the effort to automate it.

Once everything’s made it onto my desktop, and I’ve pasted those 4 builds into their folders the earlier script created, we’re ready for the next step: uploading them to the stores. Steam comes first, since it’s the biggest platform; 6 of the builds are heading there. It is possible to just upload builds through the online dashboard website, but there are limits to what it can handle, and they heavily encourage you to use their Steamworks SDK as well. It’s also setup so that you make a config file describing which files are which, and then run commands that look at those config files and do the uploading – basically forcing you to automate things anyway. The only extra step I needed to add was a script copying the builds from my releases folder to the folder where the SDK reads from. Then it’s just copying and pasting one command (well, a few commands chained together into one), wait a couple minutes, and done!

Itch is still manual uploads for each build. It also has a separate command line interface available, and honestly it’s probably worth investigating. That’s just my own fault for being lazy. (In some ways you could just call semi-automation “justifiable laziness”, haha.) Google Play is just two builds, and if there is a command line interface, it’s not at all obvious.

Overall then, this turns a painful highly error-prone process into a slightly painful less error-prone one, with relatively little effort. There’s still some low hanging fruit (zipping up and sending itch uploads, mainly), but anything else connecting those steps is going to take quite a bit more effort. It also means you understand the process better, and can more easily pick up on issues: if something goes wrong, just look at the last task you ran, rather than digging through a full confusing pipeline to find the one issue. Especially in the context of “solo” game development, I think that it’s the sweet spot.

Intermission: I’m partway through writing this dev diary, and it looks like it’s gone on way longer than I thought it would, oops. I did promise to talk about an example from Project OY, so instead of going back up and deleting that promise, I’m going to follow through and make it way too long.

Now, project OY. Despite the use of the Z dimension in this game, I’m still making and using pixel art. To animate something in pixel art, a common method is a spritesheet: basically draw every individual frame, line them up in one image, and then in the game engine specify which section is which frame. Just like with the Iron Village builds though, we’ve got some multiplication coming in. For people/characters in the game, they can be drawn in six different directions: the diagonals, straight forwards, and straight back. Right now, since I’m just getting the very basic gameplay framed out, there’s only two animations with four frames each. That’s still 48 different sprites that need to be sliced out of the sprite sheet and organized into separate animations.

I did try a plugin someone else made for importing images directly from Aseprite (the program I use for making pixel art), but it didn’t quite meet my requirements and had a few bugs. After sinking a lot of time into trying to modify it, I realized my best option would be to pull back and make something myself. Sure it won’t be as powerful as the existing tools, but it doesn’t need to be. Instead of automatically reading from Aseprite file, I can export the spritesheet (one extra manual step), and write a much simpler plug-in up to slice up and organize it.

That’s in progress right now, if people are interested I could probably generalize the logic and release the plugin. Either way though, it’s a fun little sidequest to work on.

Leave a Reply